Artificial intelligence in Accounting

In the latter part of 2013, I noticed several new developments in cloud accounting software. I suppose one of the key advantages of cloud accounting software is that it allows the software provider to concentrate on what they do well, while at the same time allow other software providers to integrate with their products. And, some of these products include some level of artificial intelligence.

To give an example of a non-cloud product first, Irish firm OCRex use optical character recognition to help accounting practices do bank reconciliations when smaller clients don’t do this – see http://www.ocrex.com/home. This software reads scanned bank statements and reconciles opening and closing closing balances, and leaving the accountant with the job of checking for missing items only. Thus, this product is intelligent in that it matches items on the bank statement using amounts and other information like to a reference.

Now let’s take this idea to the cloud. Several accounting software products can now scan emails., faxes and scanned documents to determine not only the amount of a business transaction, but also determine what kind of transaction it is. For example, xero software offers an add-on which reads transactions and posts automatically to the correct expense account. From my understanding of the xero add-on, it also learns as it goes, learning what supplier is posted to which expenses account etc. This certainly has a lot of potential for small businesses, reducing processing time and storing documents in the cloud.

What is the margin on the Apple iPhone 5S and 5C?

This is a question I often asked, well about all iPhone models since my iPhone 3. Below is a link to a post by Wendy Tietz which includes good estimates. It is set out like a student exercise too, so give it a go if you have the time. Seems Apple make quite a margin, and it seem the mobile operators subsidise quite a bit too.

The cost of my time…

In November last year I wrote about hidden costs. You may have seen this story below doing the rounds in the internet. It made me stop to think for a while – a hidden cost of work perhaps!

“A man came home from work late, tired and irritated, to find his 5-year old son waiting for him at the door.

SON: ‘Daddy, may I ask you a question?’

DAD: ‘Yeah sure, what it is?’ replied the man.

SON: ‘Daddy, how much do you make an hour?’

DAD: ‘That’s none of your business. Why do you ask such a thing?’ the man said angrily.

SON: ‘I just want to know. Please tell me, how much do you make an hour?’

DAD: ‘If you must know, I make $50 an hour.’

SON: ‘Oh,’ the little boy replied, with his head down.

SON: ‘May I please borrow $25?’

The father was furious, ‘If the only reason you asked that is so you can borrow some money to buy a silly toy or some other nonsense, then you march yourself straight to your room and go to bed. Think about why you are being so selfish. I don’t work hard everyday for such childish frivolities.’ The little boy quietly went to his room and shut the door.

The man sat down and started to get even angrier about the little boy’s questions. How dare he ask such questions only to get some money?After about an hour or so, the man had calmed down and started to think:Maybe there was something he really needed to buy with that $25.00 and he really didn’t ask for money very often The man went to the door of the little boy’s room and opened the door.

‘Are you asleep, son?’ He asked.

‘No daddy, I’m awake,’ replied the boy.

‘I’ve been thinking, maybe I was too hard on you earlier’ said the man. ‘It’s been a long day and I took out my aggravation on you. Here’s the $25 you asked for.’

The little boy sat straight up, smiling. ‘Oh, thank you daddy!’ he yelled. Then, reaching under his pillow he pulled out some crumpled up bills. The man saw that the boy already had money and started to get angry again.The little boy slowly counted out his money, and then looked up at his father. ‘Why do you want more money if you already have some?’ the father grumbled. ‘Because I didn’t have enough, but now I do,’ the little boy replied. ‘Daddy, I have $50 now. Can I buy an hour of your time? Please come home early tomorrow. I would like to have dinner with you.’ The father was crushed. He put his arms around his little son, and he begged for his forgiveness.”

Stick to the cooking – restauranteurs and accounting knowledge?

In October of this year, Michelin star chef Derry Clarke had a go at Dublin restaurants selling “cheap meals” – see here. I guess Clarke was thinking from his own view when he said “the number of restaurants offering meal deals at economically non-viable prices just isn’t sustainable, it’s the same cost in McDonalds, but we have all of the overheads”.

He may have a point about the number of restaurants being sustainable, but Derry, stick to the cooking. Any management accountant could figure out that even if meals are sold cheap (and I doubt they are below cost as Clarke suggests), they still make a contribution towards overhead costs. It would be better to have 50 guests in a restaurant earning a contribution of €5 a head (€250 in total) than having an empty restaurant. In the latter case, costs such as labour, heating, rent and so on are still incurred.

What cost can you sell at?

In this post, I recount a conversation I had with a great mentor some years ago. It questioned my notion of what costs are relevant and how to set prices once a plant/factory is not at full capacity.

In a factory ( or any business perhaps ) when there is free capacity we can start to look at the make up of costs a little closer. Traditionally, management accounting would suggest we should at least cover all variable costs in the selling price. But think about it like this – if we have spare capacity, then perhaps the only additional cost is the material cost. Let’s assume we have a machine with a full crew, but not at full capacity. The fixed costs of the machine are just that – fixed, and we cannot avoid them. The labour costs are in effect fixed too, as workers will be paid. So, in this case, only the material costs are relevant. And this, any selling price above the material cost contributes to profit.

Yes, there may be many simplistic assumptions in the above. However, it made me think back then and I always give this example to my students. It is of course an example of throughput accounting, which I will mention next week.

Related articles

Product development and advertising costs

It’s probably fairly obvious that product development costs affect the overall profitability of any product. Some products like drugs and new technology incur huge development costs. New technology, at least at the consumer end, often incurs huge advertising and promotion costs too. And simply, if sales are not sufficient, then losses occur.

As an example, consider a report from the Irish Times on Microsoft’s efforts in the tablet market.

“Microsoft’s Surface tablets have yet to make any profit as sputtering sales have been eclipsed by advertising costs and an accounting charge, according to the software company’s annual report.

The two tablet models, introduced in October and February to challenge Apple’s popular iPad, have so far brought in revenue of $853 million, Microsoft revealed for the first time in its annual report filed with regulators yesterday.

That is less than the $900 million charge Microsoft announced earlier this month to write down the value of unsold Surface RT – the first model – still on its hands.

On top of that, Microsoft said its sales and marketing expenses increased $1.4 billion, or 10 per cent, because of the huge advertising campaigns for Windows 8 and Surface. It also identified Surface as one of the reasons its overall production costs rose.

The Surface is Microsoft’s first foray into making its own computers after years of focusing on software, but its first attempts have not won over consumers. By comparison, Apple sold almost $24 billion worth of iPads over the last three quarters.”

(Above is copyright of Irish Times/Reuters)

Management accountant’s travelogue – part 3 – to toll or not to toll?

As I drove through France and Spain on my holiday, I thought about the tolls one must pay (on most) motorways. I was thinking how do they set the prices of these tolls? Of course, public infrastructure like motorways is often now financed by a combination of public and private investment. Regardless of the investment type, can you imagine how tricky it is to pitch a price for a motorway toll. If it’s too high, less will use it (M6 Toll in the UK) and costs take much longer to be recouped. Set it too cheap and it floods with traffic, which in turn eventually results in less users, and that equals less money. Should the price be set with future investment and on-going maintenance in mind. Should it be a social good with a very low price – but then where will the money come from for re-investment? Lots of questions here, but I hope you can see a lot of management accounting is behind these decisions. I would imagine getting the initial price correct is the toughest part. Nowadays though, I am sure there are plenty of modelling tools to help toll operators and governments.

Management accountant’s travelogue- part 1 – free ferry trips

Sorry about the somewhat cheesy title ! This summer, I spent about 3 weeks on a driving holiday in France and Spain. I love driving to Europe – no airports, luggage limit is a much as you can carry in your car, and you can stop when you want where you want. I drove just over 3,000 miles and stayed in some beautiful places. During my journey, the old business brain was not completely switched off so I’d like to share some things I noticed and thought about. Of course, they will be related to management accounting one way or another.

The first thing I noticed was that the ferry trip to France gave us a free trip to the UK. A free something is nothing new – you can lots of examples of free products, two for three deals etc. in books like Freakonomics and Undercover Economist. The deal was simply I got a free trip in a car ferry to the UK for a car and 2 adults once I completed my trip to Europe. On my return, I phoned and all went perfect. I had to pay a small amount for the kids, but we got the dates we wanted. So how much is this promotion costing the ferry company. I guess there are two ways of looking at it:

1) it costs them the lost revenue from two other paying passengers with a car – so a sort of opportunity cost

2) it costs nil, and in fact increases contribution.

Which one would you use if you were making the decision/reporting to management ? I’d go with the second view, especially in off-season. The ferry in question hardly ever leaves the Irish Sea – going back and forward to the UK three times every 24 hours, all year round. In off-season, the boat is not full – but the costs of running it are the same – both fixed and variable costs. Thus, any extra monies I spend – buying food for example – reduces the fixed costs burden. If I were to think about this free trip in full cost terms, I would probably not offer it to passengers as the fixed cost are unlikely to be covered. This would be the wrong decision in my view, as anything that contributes to the bottom line is better that nothing, or suffering the fixed costs regardless.

Tune in over the coming weeks for some more holiday stories.

Managers should know the numbers

At the end of June this year, Michael O’Leary from Ryanair was his usual self at the Paris Airshow. He let a few jibes fly at almost everyone. He also signed an order with Boeing for new aircraft, worth around $1.5 billion. Plans for future aircraft purchase were mentioned too and O’Leary compared two possible aircraft – one from Boeing and one from Airbus. While he suggested both were similar aircraft, the Boeing has 9 more seats and he said ‘that’s worth a million bucks’. When I read this , I thought is this just another quip or does we know his numbers well?

So, here are my calculations:

9 seats at average revenue of €70 = €630

Assume four flights per day per aircraft, so 630 x 4 =€2,520.

Finally, assume 360 flying days per year, this gives 360 x €2,520 = €907,200.

Let’s not argue over the rounding, and maybe my sums and assumptions are not correct. But a round €1million per aircraft per annum adds up to a lot of money. So although O’Leary’s rule of thumb may seem like a quip, it seems to be quite a good rough measure. He is an accountant after all!

What is activity-based costing?

You may have heard of activity-based costing (or ABC), and here I will try to explain the basics of ABC. First, just a short reminder of the types of cost an organisation may have.

Costs are often classified as fixed or variable. Variable costs change in line with volume/output, and are often called direct costs as they can be attributed easily to a product or service. Fixed costs, often called indirect costs, do not change when business output changes. For example, a fixed cost might be rent of a premises or the salary of a general manager. Such costs cannot be easily traced to a product or service. However, if no effort is made to trace fixed costs to products or services, then the business does not know the full cost. This makes decision-making more difficult.

Traditionally fixed production costs are absorbed into a product by means of a rate per labour hour. For example if overhead was planned at €1 million for a year and 100,000 labour hours were to be worked, then each labour hour would mean a €10 overhead cost. So a product taking two labour hours to make would be charged €20 overhead.

The traditional method can be criticised as over the years more and more overhead has been non-production type overhead and not related to the number of labour hours spent making a product – indeed automation of production in many industries has seen labour being of decreasing importance.

Another more modern way to allocate overhead to products is using ABC. The key in ABC is the word “activity”. In ABC, we can think of an activity as a collection of tasks which are linked in terms of being an overhead cost. For example, customer service, facilities management, quality control and machine setup are all examples of activities. The resources of the activity are determined, which are used to determine the cost of the activity – typically for a year. Then, what causes these resources to increase or decrease is determined. This is called a cost driver. For example, more complaints from customers will increase the resources needed by a customer service department. Using the cost driver, the overhead cost driver rate can be determined. Here’s a brief example:

A design department costs €100,ooo per annum – costs such as salaries, design materials, computer running costs etc. The more designs for new products the greater the cost, this designs are the cost driver. Lets assume there are 5,00o designs per annum, thus the cost driver rate is €20 per design. A product which needs say three designs will thus incur a €60 overhead costs for designs using ABC. If a product has nor designs, then zero overhead is incurred.

In a business, design (as per the above example) may just be one cost driver. Thus, the more resources (activities) consumer by a product the higher the overhead cost. This seems to make a lot of sense, and thus ABC is often used where overhead costs are not easily traced using direct labour hours (or similar) as a means to allocate overhead cost.

With ABC, all direct costs are assigned to the product/service in the same way as traditional costing methods. It is just the allocation of overheads that differs. Typically, ABC considers not only production overhead costs, but many other overhead costs which can be defined within activities.

Related articles

- Two activities for ABC and the appropriate cost drivers for those activities (globalexperts4u.wordpress.com)

- Introducing Overhead Cost (thebangaloresnob.wordpress.com)

CVP in farming

As you may know CVP analysis looks at costs, revenues and volumes to determine things like at what output level a business will break even or make a certain profit. This post provides a simple example of the effects of volume on the viability of a business.

Recently, a local authority in Dublin, Ireland announced plans to build a large sewage treatment in the north of the city. As part of this, a vegetable farmer in the area will lose 35 of his 120 or so acres to the plant. I listened to a radio broadcast where the farmer simply said this is too much land to lose and his operation becomes uneconomic.

Let’s think about this briefly in CVP terms. If we assume a stable price for the farmer’s products and stable variable costs (seeds, labour, fuel, fertilisers for example), then it would seem that a loss of about 25% of capacity would reduce the farmer from a profit scenario to a loss one. I am not an agricultural expert, but I would assume that the fixed costs consist largely of the equipment and buildings needed to operate the farm. If the land area is reduced (i.e. capacity is reduced), then the farmer simply does not have enough land left to produce enough revenue to cover these fixed costs and make a profit.

You can read more here.

US Postal Service – reduced volumes = reduced costs

In February this year, the United States Postal Service (USPS) decided to cease delivering mail on Saturdays. While this may be seen as inconvenient for some personal and business users, in management accounting terms it is probably a simple cost-volume issue.

Mail volumes have fallen globally due to email and other communications media. With falling volumes, a postal service would either have to reduce costs or increase revenues to maintain profits – or keep state subsidies low. Increasing revenues may be difficult given the competition is sectors such as parcel deliveries, which have increased in volumes. It is also difficult to raise postage rates given the political and/or state involvement. So this leave costs, or more specifically cost-cuts, to get things back in balance. Apparently, ceasing Saturday deliveries will save $2 billion annually. You can read more here from The Economist

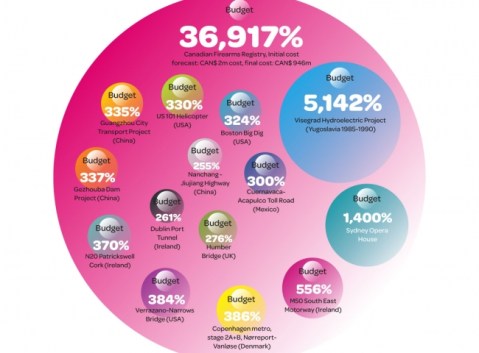

Cost overruns on projects

Here is a great infographic from the February edition of CIMA’s Financial Management. A few Irish projects in there. I think we’re better nowadays, but I may stand corrected on that.

Read the full article at this link:

15 of the world’s biggest cost overrun projects | CIMA Financial Management Magazine.