Speed cameras business

In July this year (2013), I read an interesting brief news report about a speed van operator in Ireland. Yes, we all hate these guys, but the article made me realise this seems like a good business to be in – even if you are hated by motorists. According to the article, the GoSafe consortium makes a profit of almost €50,000 per week or €2.5m per year. It has almost €11m debt and is contracted to provide 6,000 hours per month to the Irish state. The article notes that at least one motorist per hour is caught speeding. I don’t know the ins and outs of the contract, but if the company makes a profit of €2.5m annually, even if it does pay out some dividends, the debt owing could be paid down quickly it would seem. The management accountant in me would really like to know what is the breakeven number of speeding motorists per day! You can read more at this link: http://www.rte.ie/news/2013/0720/463662-speed-vans/

Management accountant’s travelogue- part 2 – merendero

While in Northern Spain – Asturias to be exact – we were invited one evening to a meal at a merendero. From my limited knowledge of Spanish, this translates loosely to a picnic area. What we in fact had was a lovely tapas evening in a restaurant with a merendero attached. I have written before about business being child-friendly, or not as is often the case. The merendero concept is so simple; a lot of picnic tables, some play areas/equipment, a simple ordering system where you collect you food. And, all this at minimum cost to the restaurant I would imagine – at least in fixed costs. On the revenue side, the turnover of the restaurant is probably increased quite a bit as 1) more parents come and 2) future customer (the kids) are secured. In the particular merendero we visited, there were at least 100 places outside for people to eat and drink – a sizeable increase in volume without equally high costs. If only the Irish weather were good enough to do this! But, I’m sure a clever restaurant owner could take some of the idea and increase their business success (and revenues).

The best private companies do …what exactly to be successful?

Short post this week , but no less interesting I hope. Here’s a link to a nice article on Forbes which gives the key habits of successful private companies. Article

CVP in farming

As you may know CVP analysis looks at costs, revenues and volumes to determine things like at what output level a business will break even or make a certain profit. This post provides a simple example of the effects of volume on the viability of a business.

Recently, a local authority in Dublin, Ireland announced plans to build a large sewage treatment in the north of the city. As part of this, a vegetable farmer in the area will lose 35 of his 120 or so acres to the plant. I listened to a radio broadcast where the farmer simply said this is too much land to lose and his operation becomes uneconomic.

Let’s think about this briefly in CVP terms. If we assume a stable price for the farmer’s products and stable variable costs (seeds, labour, fuel, fertilisers for example), then it would seem that a loss of about 25% of capacity would reduce the farmer from a profit scenario to a loss one. I am not an agricultural expert, but I would assume that the fixed costs consist largely of the equipment and buildings needed to operate the farm. If the land area is reduced (i.e. capacity is reduced), then the farmer simply does not have enough land left to produce enough revenue to cover these fixed costs and make a profit.

You can read more here.

Big data and business decisions – humans still needed

Here is a good article from CGMA magazine which highlights the importance of human interpretation of data. It is a reminder that although we have technology to analyse data which we could not do ourselves, we still need the human eye to make sense of data trends etc. and relate it to organisational context.

Related articles

- Infographic: The Physical Size of Big Data (domo.com)

The problems with big data?

The previous two posts have hopefully given you a very brief insight into what big data is and how it can help even small organisations. Now let’s briefly consider larger organisations. Nowadays, even if a company like amazon can process a few million orders a day, the amount of accounting data associated with this (i.e. a few million invoice and a few million payments) seems insignificant if we start to think about other data that might be collected at the same time. For example – and these are just a guess on my part – the age, sex, location of the purchaser, the type of device they searched and bought on, what the looked at before buying etc. The amount of data starts to get really, really big.

A report by Deloitte includes two quotes that capture the perceptions of big data really well:

“Big data is the new oil. The companies, governments, and organizations that are able to mine this resource will have an enormous advantage over those that don’t.”

“Big data will generate misinformation and will be manipulated by people or institutions to display the findings they want.”

(Source: The insight economy Big data matters— except when it doesn’t, Deloitte, 2012, available at link above)

As the report says, both the above perceptions are right. The key things about big data is getting information out of it and transforming that information into business knowledge. In other words, like many other things organisations encounter on a regular basis, big data needs to support the organisation’s strategy. This may mean being more competitive, gaining some market knowledge before others or opening up new business channels. Whatever big data might mean for larger (and smaller) organisations, I believe management accountants in particular have a key role in making in useful information/knowledge – after all, we are good at analysing information and filtering out what is relevant.

Related articles

- The future of big data (infographic) (siliconrepublic.com)

Kindle Fire breaks even – but profits elsewhere

I have written a few posts before on breakeven, but here is a great example of how businesses are prepared to accept not making money on some products, for the sake of others. In October 2012, Amazon launched its Kindle Fire tablet and its Paperwhite e-reader in the UK and other European countries. The Kindle Fire retails at about £150, which is probably less than half the price of an iPad and about £100 cheaper than an iPad mini. In an interview with the BBC , Amazon’s boss Jeff Bezos said the company sells its hardware at cost i.e. they breakeven. This may explain the cheaper price of the Kindle Fire compared to the iPad. However Amazon earn profits on Kindle book sales, Kindle book rentals and its Prime service. In contrast, Apple have noted they breakeven on services such as iTunes and make profits on their hardware,

Technology and new business-models – taxi despatching

I always like to read about new ways of doing business, or new technology can change existing businesses. You may have seen how various new technologies have helped the taxi-sector. For example, in London you can send a text from a smart phone requesting a taxi and your position can be pin-pointed by the GPS within the phone. Now let’s take this a step further and add an app to the smart phone and then the way the whole taxi industry operates could change? How you might ask. This post from the Babbage blog on Economist.com explains why. In several European countries, taxi users can now use apps to request a taxi. The apps ping the nearest cab, and once a customer accepts a particular offer they can track the taxi progress. All the taxi needs is the same app effectively. This changes the way business is done in the sector as the taxi dispatcher is effectively cut out of the picture. I don’t know about other cities, but I can tell you that a taxi dispatcher would charge its drivers in the order of €200 per week or more in Dublin. For this, the driver (who suffers all risks of owning and paying for the cab) gets fares directed to them usually through some system installed in their cab. Now, if I were a self-employed taxi-driver you could cut out that cost by using an app, I’d be giving it some serious consideration. Of course, as the post notes, taxi dispatchers are not seating idle and a race is on between taxi dispatchers and app developers!

Facebook price earnings

I have written before about key financial ratios which can be used to analyse a business. Here is a great current example – the price earnings ratio for Facebook. The post is from a New York Times blog.

The effect of volume on viability – a CVP and investment example

In January 2011, a long-planned €350 million plan to build a 600,000 tonne incinerator near Dublin port finally seen work commence on the build. As you might imagine there have been many protests against the project, which would be privately operated. At the same time, the four Dublin local authorities were also planning a land-fill site north of the city. However, in January 2012, the Irish Times reported that the land-fill site plan has been scrapped. It seems that the volume of waste now being generated in Dublin does not merit a new land-fill site. And, indeed the need for the incinerator too is being questioned. It seems that due to a combination of increased recycling and lower economic activity that the volume of waste has decreased dramatically. As a management accountant, I think of this from two angles. First, from a capital investment view, someone had to decided the ultimate size of an incinerator. This would be based on a combination of commercial viability and waste volume I assume. Second, from a cost-volume-profit (CVP) view, I wonder has anyone considered the effects of volume on the “profit” (i.e. viability) of the incinerator. According the to the Irish Times article, the volume of the incinerator should be halved – which I think should mean a full re-examination of the costs and investment involved. Of course, the counter argument is it is better to have spare capacity for cover for future increases in waste generated (e.g. improved economic activity, increasing population)

In January 2011, a long-planned €350 million plan to build a 600,000 tonne incinerator near Dublin port finally seen work commence on the build. As you might imagine there have been many protests against the project, which would be privately operated. At the same time, the four Dublin local authorities were also planning a land-fill site north of the city. However, in January 2012, the Irish Times reported that the land-fill site plan has been scrapped. It seems that the volume of waste now being generated in Dublin does not merit a new land-fill site. And, indeed the need for the incinerator too is being questioned. It seems that due to a combination of increased recycling and lower economic activity that the volume of waste has decreased dramatically. As a management accountant, I think of this from two angles. First, from a capital investment view, someone had to decided the ultimate size of an incinerator. This would be based on a combination of commercial viability and waste volume I assume. Second, from a cost-volume-profit (CVP) view, I wonder has anyone considered the effects of volume on the “profit” (i.e. viability) of the incinerator. According the to the Irish Times article, the volume of the incinerator should be halved – which I think should mean a full re-examination of the costs and investment involved. Of course, the counter argument is it is better to have spare capacity for cover for future increases in waste generated (e.g. improved economic activity, increasing population)

Costs, volume and profits – an example from the taxi sector.

Back in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s when I was young enough to be frequenting pubs/clubs around Dublin city centre, one of the biggest problems was getting a taxi home. At that time, the number of taxi’s was regulated, with (if my memory serves me right) about 1,200 taxis for a city of about a million people. The effect of this was a market for taxi licences. Many taxi drivers depended on this for their pensions, with a licence yielding IR£ 60,000- 80,000 (about €75-100,000). Now, Dublin has a de-regulated taxi system and has more taxi’s than New York (see here for a taxi-eye view). The price structure is also heavily regulated, and a common price structure applies to all fares throughout Ireland. And, of course, a taxi licence is nowadays worth very little.

Back in the late 1980’s and early 1990’s when I was young enough to be frequenting pubs/clubs around Dublin city centre, one of the biggest problems was getting a taxi home. At that time, the number of taxi’s was regulated, with (if my memory serves me right) about 1,200 taxis for a city of about a million people. The effect of this was a market for taxi licences. Many taxi drivers depended on this for their pensions, with a licence yielding IR£ 60,000- 80,000 (about €75-100,000). Now, Dublin has a de-regulated taxi system and has more taxi’s than New York (see here for a taxi-eye view). The price structure is also heavily regulated, and a common price structure applies to all fares throughout Ireland. And, of course, a taxi licence is nowadays worth very little.

Why and I writing about taxis you might ask? Well, while on holiday near Leipzig (Germany) over the Christmas period, I read an article in a local paper (Doeblener Allgemeine Zeitung, Dec 27, p.7) about how a taxi firm is dealing with rising costs. The taxi sector in Leipzig is de-regulated too as far as I know, and competition is strong. The article interviewed a manager from a local taxi firm, 4884. Rising fuel prices seem to be a major problem for the firm – and indeed for Dublin taxis too. However, as I read on I realised that Dublin and Leipzig taxi firms/owners, while having a lot in common (over/high supply, rising costs, relatively declining static/declining market), the Leipzig firm 4884 seemed to adapt well to become attract and keep customers. For example, in June 2011, 4884 launched an app to order taxis (using GPS). They also (according to the Dec. article) regularly train and annually update their drivers on things like customer service skills – it is even written into the drivers’ contracts. In Dublin too, there is at least one taxi app I am aware of (Irish Taxi), but I am not sure it is as advanced in terms of GPS. London too has a GPS service available for ordering a taxi.

So what’s the management accounting point? Well, if we compare the market for taxis now to compared to the past (in most countries, but certainly Ireland), there is a far greater supply (volume). The cost structure is typically beyond the control of all taxis. Most costs are fixed – radio rental, advertising, taxi licence fee, insurance – with fuel being the main variable cost. With more taxis in supply, a static market, fixed prices and little ability to control costs, then the ability to earn a profit is likely to be more difficult now. So what can be done by taxi owners/firms to sustain profit. Most have joined forces to create firms/co-ops, which can share some costs (e.g. central booking). Other options are to increase customer retention through things like apps and improved customer service. At the end of the day, with so many costs beyond their control, taxi drivers/firms can only but be adaptive to stay in business. If they are not, they can (and do) go out of business.

Does accounting prevent creativity and innovation?

Accounting is often criticised, and one of the common criticisms is that too much focus on money in a business causes a short-term focus which may not be good for a business. I would agree to an extent, probably because I am more into management accounting and have seen businesses take bold decisions which eventually paid off. Of course, financial accounting (the external reporting of results basically) is less helpful (or “completely useless” as one business owner told me a few weeks ago) in situations where decisions need to be made. And sometimes, these decisions involve a lot of brave and bold creativity and innovation which accountants seen to have a reputation of pouring cold water on.

I read two articles recently which made me think about accountants and creativity/innovation. The first one was a few months back on Forbes. The piece by Eric Savitz mentioned how creative type toys (like Lego) can be crucial to later creativity. Here’s a quote from him:

Lego, loosely translated, means “to put together” in Latin. But “to put together” doesn’t fully encompass the value – and purpose – of those buckets of colorful bricks. Legos are about putting together, then taking apart, then reassembling in new ways. That’s why I got so upset recently when a friend told me that she and her daughter had built a pirate ship out of Legos, arranged the pieces until they were just right, and then glued the whole thing together. That, I exclaimed, is not the point.

Legos unleashed my creativity when I was growing up. They drew out the part of me that had to know what things looked like from the inside out, how they worked, how they might work better. The hours I spent with them — sprawled on the floor, building and rebuilding, puzzling and visualizing — became my first lessons in engineering. There was magic in those little bricks. There still is.

Reading this I wondered how would Savitz be as an accountant. I think he would have a good chance of being creative, but not in a bad way. I think, like the Lego, he might be throwing away the rule book and creating accounting information which might meet the needs of the organisation where he was working. This of course is what good management accountants should do, but do they all? I don’t know, perhaps its partially our fault (i.e. educators) and we need to encourage lateral (but always ethical and proper) thinking about accounting.

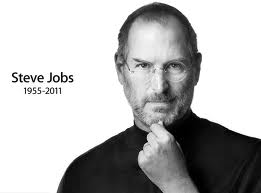

The second article I read was in this week’s Time, “What would Steve do?”. Steve Jobs was an obviously brilliant innovator – and eventually made Apple one of the richest firms in the world. In the article the author (Rana Foroohar) makes a strong claim, but she is probably fairly correct. She states ” Jobs stands out as an exceptional leader not so much because of his in-your-face style, but because American business has become dominated by bean-counters focusing on hyper-efficiency rather than by innovators focused on real growth”. I suppose this is a classic case of too much focus on short-term financial goals over longer-term business development and growth. I don’t have a quick-fix solution for such a problem, but certainly an open mind by accountants towards innovators would help.

What is a “business model”?

Often, when I teach about types and classifications of cost in my management accounting classes, I use the term business model. For example, I might say “whether a cost is fixed or variable, can depend on the particular business model”. But, I am assuming the term business model is well understood. Perhaps it is not, and even when I asked myself what the term means, I had to do a bit of thinking. So here’s a simplified explanation.

Often, when I teach about types and classifications of cost in my management accounting classes, I use the term business model. For example, I might say “whether a cost is fixed or variable, can depend on the particular business model”. But, I am assuming the term business model is well understood. Perhaps it is not, and even when I asked myself what the term means, I had to do a bit of thinking. So here’s a simplified explanation.

An article in the Harvard Business Review from 2002 describes a business model as “the story which explains how an enterprise works”. This is a deceptively simple definition, but it does capture exactly what a business model is. If I were to ask you what are the essential elements of a story such a Cinderella or The Frog Prince, you would probably says things like characters, what the characters do, when the characters do things, and of course the (moss likely) happy outcome. Using the story analogy, a business needs to ask itself, what is that we do, who are our customers, how much does what we do cost, and will we make money (the happy outcome!). In other words, “what’s our story” in an economic sense (Read the full HBR article for more detail and examples).

Nowadays, business models have become a bit blurred though. For example, there are so many web-based “businesses” out there who, to be honest, do not immediately show a story which makes economic sense. For example, we now know how Google and Facebook can make money on a business model which changed the advertising world. But, what about for example Twitter or off-shoots like paper.li. I love the latter, as I can bundle all the twitter users I follow into a daily newspaper, but how can this make money. I am guessing they will introduce advertising, but has this business model already been over-cooked?

I hope this helps you understand what a business model is. To conclude, I suppose the story of what it is a business does has to be infused with accounting concepts. For example, there is not point being the world’s best at something, but costing a fortune to do it.

Gearing ratio – 6 of 6 in series on financial ratios

In this last post on financial ratios, I will look at some ratios which are of interest to the providers of debt finance i.e. lenders like banks and investors who buy debt in companies instead of shares. We will look at two ratios, the Debt/Equity ration and Interest Cover.

The Debt/Equity ratio is calculated as follows:

Debt/Equity ratio: Debt

Equity

Debt is long-term debt, which is normally taken to mean long-term bank loans and other debt finance found under the non-current liabilities heading in the statement of financial position (balance sheet). Equity is the shareholders’ equity, or the capital provided by or attributable to shareholders (typically share capital, accumulated profits and other equity reserves). In general, if the gearing ratio is greater than 1:1, then a business is said to be lowly-geared; less than 1:1 makes it highly-geared. For a potential investor or lender, the higher the level of gearing the more risky the business may be. From a potential shareholder’s view, if more cash is needed to pay interest on debt, less is available for dividends. From a lender’s view, if the level of existing debt is high, repaying any additional debt may be problematic. However, high gearing is not necessarily a bad thing. Once monies borrowed are put to good use and earn a return greater than the rate interest paid, overall company profits grow. Managers use investment evaluation techniques to select investments (such as building a new production facility) which will produce returns beyond the cost of borrowing.

The next ratio, Interest Cover, is useful to lenders in particular. It is calculated as follows:

Interest Cover: Operating profit

Interest

The interest cover ratio simply tells us how many times operating profit (which is before interest, tax and dividends) covers interest. From a lenders perspective, a higher level of interest cover is preferred. If the interest cover is low, then a business might have trouble meeting interest payment on borrowings, which certainly would not bode well for repayments of the principal (the amount borrowed).

As in previous posts, let’s now calculate these ratios based on the financial statements of Diageo plc for 2010. The Debt/Equity ratio is as follows:

8177/4786 = 1.7:1 (data from p.108)

This means Diageo plc is a highly geared company. It is however quite successful and generally pays dividends to shareholders, so it most likely uses its debt well.

The interest cover is:

2574/844 = 3.04 times.

This means profit covers interest payments just over three times at current levels, which is reasonable.

Investment ratios – 5 of 6 in series on financial ratios

As we have seen in an earlier post the ROCE may be useful to shareholders, but there are a number of other ratios which they may find particularly useful as investors. These are Earnings per Share (EPS) and Price Earnings (PE).

As we have seen in an earlier post the ROCE may be useful to shareholders, but there are a number of other ratios which they may find particularly useful as investors. These are Earnings per Share (EPS) and Price Earnings (PE).

EPS represents the profit per individual share. It as calculated as follows:

EPS: Profit after tax, interest and preference dividends

Number of ordinary shares in issue

The top portion of the EPS ratio represents the profit that is available for payout as a dividend. This does not at all mean it will be paid out, but it is the profit available to ordinary shareholders. Given that the bottom portion of the EPS is the number of ordinary shares issued, the EPS is not very comparable between two companies. However, the trend of the EPS of a particular company is an important indicator of how well the company is performing and it is also an important variable in determining a shares price

The PE ratio shows a company’s current share price relative to its current earnings – which assumes the company is a public company and its shares are available for purchases through a stock market. It is calculated as follows:

P/E ratio: Market price per share

Earning per share

It’s usually useful to compare the P/E ratios of one company to other companies in the same industry, to the market in general, or against the company’s own P/E trend. It would not be useful for investors to compare the P/E of a technology company (typically high P/E) to a utility company (typically low P/E) since each industry has very different growth prospects. Care should be taken with the P/E ratio because the bottom part of the ratio is the EPS, which as stated above may not be that comparable between companies. There are some crude yardsticks for the P/E ratio as follows:

- A P/E of less than 5-10 means that company is viewed as not performing so well;

- A ratio of 10-15 means a company is performing satisfactorily;

- A ratio above 15 means that future prospects for a company are extremely good.

Again, as with all such yardsticks, these will vary by industry and depend on other factors which drive share price e.g. bad publicity, the general economic outlook.

As in previous posts, let’s use the accounts of Diageo plc from 2010 to calculate these ratios.

EPS = 1,762,ooo/2,754,000 = £0.64 per share (data from p. 107/150)

PE = 1060/64 = 16.6 times (share price from http://www.diageo.com/en-row/investor/shareprice/Pages/Shareprice-History.aspx. Based on the yardstick mentioned above, the PE for Diageo reflects sound future prospects.