So what is big data?

Big data has been the feature of many articles in professional accounting journals such as CIMA’s Financial Management. But what exactly is big data? Originally it referred to more data than information systems could process. But today we have systems capable of processing and analysing millions of transactions in seconds . So what does it mean now? Well, I think the answer to this question will depend a lot on who you ask. To me big data is still data analytics, with maybe some external or social data sources thrown in., with a defined purpose of adding value or saving resources (such as cash or time). This is of course a very broad understanding of what big data is, as value will not mean the same thing to all organisations.

I read an article on Forbes recently which has a similar approach to big data as that I suggest above. The key point the author notes is not to care too much about defining things like big data, but to remember “who cares”. To quote directly from the article “the goal should be to solve a business problem by using new analytics, not to worry about defining a term. That’s because definitions are a distraction from the simple question of “Does this data contain information that is valuable for my business?”

How low-cost airline reduce costs and change our behaviour

I’m a bit tight on time today, so here is a link to a nice article the Economist which gives some useful insights and summaries of how low cost airlines have reduced costs over time. Enjoy.

The cost of “non-local” food

A while ago, I was asked to write some entries for an Encyclopaedia of Corporate Social Responsibility. I enjoyed this and the research behind the writing. One of the terms I wrote about was Local Food. Without repeating the definition verbatim, local food is basically food grown within a local area. But what exactly is local? Town, region, state, country or what? That’s the hard part.

The image to your right shows some nice juicy strawberries. When I was a kid, we had these as treats from about May to July. And they are a treat, once in season and local. But now I can get strawberries at Christmas – but they taste c**p usually and come from many miles away. This is definitely not local food.

Bringing consumers year round fruit (and other food types) is an expensive and difficult business. An article in the November edition of National Geographic gives some idea. Yes the example is US based, but it has some hard facts. The article follows the 3,200 mile journey of strawberries from California to Washington DC. The berries are grown on large-scale farms and over 500 trucks a day can be involved on just one farm. The retail value of each truckload is $90,000, and fuel for each truck costs $2,700. Total journey time is 80 hours, for which a driver must be paid etc, and think about the wear and tear of the truck. This is hardly a local food example I would argue, and it easy to see the money involved. And I’m not even starting on the true cost, which includes costs of large-scale farming (pesticide run-off for example) and CO2 emissions.

Managing and accounting on farms

As I come from a rural background in Ireland, agriculture has to an extent always been part of my life. I have worked on farms as a young lad, and all things agriculture interest me still.

As a management accountant, I’d have a wild guess and say that most farmers do little formal accounting – particularly small farmers. Some farms have quite the turnover nowadays in Ireland and many are incorporated and even fit the medium-sized company criteria. The smaller farm, like many small businesses, probably does very little accounting – maybe just the annual trip to the accountant’s practice to work out taxes due.

As I have written in previous posts, cloud-based accounting software is a key tool in my view in bringing accounting to small business. And farming is no exception to that. Having done a relatively brief Google search, I could not readily find any cloud-based accounting apps which might be suitable for farmer. Farm accounting is a little difference than other business sectors in that 1) inventories are live crops and animals and 2) costs and revenues needs to be captured by sector e.g. tillage, dairy, crops. I have found several farm management apps, such as FarmFlo or see here for an international view. There are some software packages specifically designed for larger farms (see here for example), but it seems there is a gap there in terms of the smaller farmer. If I were to design an app, to be honest I would focus more on cash-based accounting than accruals accounting. I think farmers focus more on the cash in the bank than on profit.

Accounting can be bad for your health!

The bookkeeping end of accounting can certainly be a bit dull – even if it is the source of much accounting data. Dealing with invoices, receipts and other bits of paper is an absolutely necessity – the promised paperless office is still awaited.

An article in Forbes recently surprised me though. Apparently the thermal paper used in many till and other receipts can be quite harmful to your health. Have full read here

What is life cycle costing?

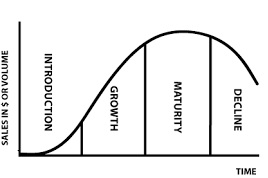

You may have seen the typical product life cycle graph in your previous studies (see left). The basic idea is that sales in money and volume increase over time, but gradually tail off as the product comes to the end of its cycle.

You may have seen the typical product life cycle graph in your previous studies (see left). The basic idea is that sales in money and volume increase over time, but gradually tail off as the product comes to the end of its cycle.

When we think of management accounting and product costing, we are generally looking at short-term costs, and not all costs a product may incur over it’s life cycle. For example, there may be advertising costs to boost sales of mature products, costs of product development or even remediation/disposal costs. Life cycle costing include all costs of a product or service from design to end-of-life. All recurring and once-off costs are included over the entire life cycle. These costs can then be compared with expected revenues to determine if a product is profitable or not.

To give you an example, consider the drug development life cycle. It may take many years and cost €billions to bring a drug to market (see here for example, which depicts the process at Bayer), before a single euro in revenue is earned. Then, there are the on-going manufacturing costs. Perhaps the drug has side effects, and needs some improvement during its life. And perhaps as the drug ends its life, there may be costs in dismantling purpose-built manufacturing facilities. Taking all these items (and more no doubt) a drug company can consider if a particular drug is profitable.

Environmental and social reporting – new EU Directive

Image from viralheat.com

I recently read an article from the Guardian which highlights the problems of measuring and reporting all things environmental, sustainable and social. The article noted a recent study n the Journal of Cleaner Production. It analysed metrics used in academic literature to measure performance in sustainable supply chains. The study reveals a total of 2,555 different metrics were published in 445 different articles.

I think we would all agree that publishing some performance measures on sustainability and similar issues is very important. But if we do not have a set of standards to follow, comparing things is quite difficult. This should sound quite familiar to accountants, as before we had financial reporting standards in the 1970’s and IFRS at EU level today it was not easy to compare financial statements.

Although there are some standards on environmental and social reporting (such as the Global Reporting Initiative), these are typically voluntary. The EU has recently provided some help and impetus. According to a CGMA article, “About 6,000 large companies and groups across the EU will be required to disclose certain non-financial information on environmental and social impacts as well as diversity policies for boards of directors”. The Directive must be implemented by member states within two years, so by 2017, we should see the first reports. I am sure some will say the Directive does not go far enough, but at least it’s a start and it sets a standard. This is better than no reporting or such diverse reporting that it becomes pointless.

Simple graphical reporting

I have written a few posts in the past on the use of infographs to get a key message or statistics across to managers. While on holiday in Germany, I visited a now disused mine and I came across this:

It is a simple graph which shows the injuries at the mine for a nine month period. It does not need much explaining. What strikes me is its utter simplicity – it gets the number across in a clear and simple manner. It should be understood by all staff from managers to workers. It’s on a single page, and drawn manually – probably pre-dates computers.

Tesco and its hello money.

Image from Tesco.ie

A few weeks ago, a news story broke about an accounting scandal at Tesco – see here for example.

So how can this happen? It’s very simple actually. Now, we don’t know if it’s an error or something deliberate, but from an accounting view the entries in the books are the same.

When I was in college 20 years ago, one of our accounting lecturers asked is how would we account for this “hello money” as he called it. Within a decade I was calculating and accounting for what were termed “long term agreements” in my role.

For the likes of Tesco, the amount involved are large and I would guess they account for hello money as a separate income stream – although it’s not shown in the published accounts. Another way would be to reduce purchase cost, but this would probably be for smaller amounts. But how can Tesco make such an error you ask? Simple, just ” over accrue”. This means recording future hello monies now. Of course, I have no idea this is what actually happened, but it does show how easy errors or manipulation can happen by using the good old accruals concept.

A new approach to cloud accounting software?

I am writing this post without using the software I mention, so apologies if I am incorrect.

Sage (a leading provider of accounts software) have recently extended their most popular product to the cloud. And they have done to in a way which seems to address a lot of concerns.

My experience of cloud accounting software is that while it is functional and easy to use, it does lack some of the capabilities that desktop accounting software offered. What Sage appear to have done is taken their best product for SME – Sage 50 – and retained the best of both worlds. The news release at the link above suggests a new product, Sage Drive, allows the user to retain the desktop functions but store data in the cloud. This has several advantages. First, the sharing capabilities of the cloud are available once the data is stored there. Second, existing functions are maintained and this may particularly suit the accountant users. Third, it may ease some security concerns accountants often mention with the cloud. From my understanding, only the data is cloud hosted. Some desktop software is still needed to make sense of the data.

Does new technology in accounting wipe out the old?

Quite a tough question above I guess. I have always been interested in what technology can do for business – both as a management accountant and academic. It is probably fair to say that the past decade has so much more technological change than previous decades. We have seen smart phones, tablets, the cloud and social media all appear and take over our lives and change how business is done.

Quite a tough question above I guess. I have always been interested in what technology can do for business – both as a management accountant and academic. It is probably fair to say that the past decade has so much more technological change than previous decades. We have seen smart phones, tablets, the cloud and social media all appear and take over our lives and change how business is done.

Personally, I am watching how accounting in small business is now potentially so much easier than ever before. For example, all a sole trader needs is a smart phone and they can issues invoices, records expense and even get paid. I would hope that over time this will become a reality. However, at the same time I am quite aware that it will be while before we see small businesses not having some manual recording.

I have also recently become a little interesting in accounting history. It has been commonly accepted that symbols used on clay tablets used by traders in ancient Mesopotamia were a precursor to modern writing. These clay tablets were in effect what we call invoices or delivery notes today. One would imagine that writing would help simplify business of the ancient Mesopotamians, and replace the symbols on the tablets. Recent archaeological finds in Turkey however suggest otherwise. It would seem the tablets and symbols survived for many centuries after paper and writing were in common use. So I wonder will it a few centuries before small businesses take advantage of the present day accounting technology ? Incidentally, it seems tablets (but not clay ones) are probably a very simple way to manage small business accounting.

CVP Analysis in action – the TGV

A few weeks ago I posted a piece on costs and profits when there is too much volume in the market. This post takes a look at the TGV (high-speed) service of SNCF. It’s in a spot of bother in terms of profit and management are considering various options.

I have been on the TGV several times. It is a fabulous service, but in today’s low-cost flight era it’s a bit expensive. And that’s exactly what a recent post from the Economist noted. According to the post, many TGV routes are no profitable. The reason for non- or low profitability is two-fold 1) increased competition from low-cost airlines who entice passengers with lower fares and 2) increasing costs paid to the rail track operator. SNCF management have apparently suggested three possible solutions, as follows:

1) decrease volume – i.e. reduce routes to those which are more profitable and attract adequate passenger numbers

2) increase volume, by lowering price. This could attract passengers back from low-cost airlines. It is a risky option though, as failure to attract enough passengers could worsen things

3) overhaul operations to be more like a low-cost airline i.e. become more cost conscious and efficient.

Which ever of the above three options are chosen, it is a classic case of the application of Cost-Volume-Profit (CVP) analysis. The costs and revenues will determine how profitable the TGV routes are, but so will the volume available. For example, using option 1 may improve profitability, but may not address costs or revenues. It may also be a bad option politically. Option 3 might keep service volume, but increase profitability and maintain pricing. And, as mentioned, option 2 might increase profitability if passenger volumes increased. It is not to hard to imagine a management accountant at SNCF using CVP techniques to show managers possible outcomes of each option.

Comparing profits and other figures from accounts

One thing really annoys me about how the media reports company performance – they only ever give % increases or decreases in sales or profit typically.

If you have ever studied accounting you probably learned about ratios analysis, and how just looking at absolute numbers ( like sales or profit ) can give a false picture. Here’s a recent example from the Irish Times to illustrate what I mean.

According to the Irish Times (see here :

“Irish-owned book and stationery retailer Eason & Son has recorded a net profit after tax of €2.3 million in its financial year to January 2014, compared with €2.6 million the previous year. Eason Group revenues, however, were down 7.1 per cent to €227.4 million, in what the company called a “challenging year”.”

All the above is true, but if we do a quick calculation, profit as a % of sales ( profit margin ) is pretty much the same from one year to another. So despite a 7% drop in sales, costs must also have been well managed to maintain a stable profit margin. I appreciate the media try to keep these reports simple for the general public, but a little more depth would be very useful.

CVP analysis – the effects of too much volume ?

Last summer I again took the car to Europe, using the Dover-Calais crossing. Not too long before I went I read an article about a UK Competition Authority ruling against one of the ferry operators – read here.

One of the operators is (now) owned by euro tunnel, hence the competition ruling. But let’s bring this to basic costs, volumes and profits. The ship I travelled on was almost empty, and as there is so much capacity on the route some operators are being pushed into a loss scenario. Why? Well, think about it for a moment – costs of running a large ferry are probably quite fixed. Prices may be low due to competition, but volume is relatively static. So, lowering price to attract passengers may be a loss maker. Similarly, too many operators may mean smaller passenger numbers for all, driving some into a loss situation.

So, as basic economics may dictate, ultimately one operator will fail as the market will force them out. And remember CVP analysis is based on a subset of the cost curves used in economics.

What is a cost centre?

If you type the above question into a Google search, you’ll get many answers. The one thing I found funny about the answers I looked at is they always mention costs – great – but some do not at all mention accountability.

So what is a cost centre? Well here is my definition. A cost centre is a unit, function, department or similar in an organisation for which:

1. Costs can be traced to

2. A manager is held accountable for those costs.

The second part of the definition is often forgotten, but it is probably the most important. The basic idea of responsibility accounting is that a manager is responsible for things like planning a budget or measuring performance against target. So in a cost centre, the manager is accountable for costs – but not revenue, profit or return on investment.