How business models can (climate) change

Following on from my last post on what is a business model, here I recount two articles I had saved from last year on how climate change can force businesses to change – and in some cases even change the business model.

Following on from my last post on what is a business model, here I recount two articles I had saved from last year on how climate change can force businesses to change – and in some cases even change the business model.

The first article comes from Time (Sep 04, 2011). It recounts how Spanish winemaker Torres are increasingly moving their crops to higher, cooler areas of Spain. Due to global warming, the hotter climate means sweeter fruit and earlier ripening. At the same time, the early ripening of the fruit is offset by the fact that the seeds and skin (which give flavour) are not ripe. Thus, as a possible solution, vines are being planted at a higher, cooler altitude in an effort to offset the warming experienced in traditional regions.

The second related article comes from The Economist (Sep 10, 2011, online). In this articles, you can read how English wine is being produced in increased volumes and better quality – with locally grown grapes. Again, it is climate change – bringing warmer climes to Southern England – meaning that more traditional grape varieties can be grown in England as opposed to the typically acidic German varieties. The result has been a product of increasing quality, and a tendency to produce higher margin sparkling wines – something that was not so easily done before. Thus, the business model of English vineyards may have changed from one where imported “grape juice” was added to make local wine, to one where high quality, high-margin product is the norm.

Does accounting prevent creativity and innovation?

Accounting is often criticised, and one of the common criticisms is that too much focus on money in a business causes a short-term focus which may not be good for a business. I would agree to an extent, probably because I am more into management accounting and have seen businesses take bold decisions which eventually paid off. Of course, financial accounting (the external reporting of results basically) is less helpful (or “completely useless” as one business owner told me a few weeks ago) in situations where decisions need to be made. And sometimes, these decisions involve a lot of brave and bold creativity and innovation which accountants seen to have a reputation of pouring cold water on.

I read two articles recently which made me think about accountants and creativity/innovation. The first one was a few months back on Forbes. The piece by Eric Savitz mentioned how creative type toys (like Lego) can be crucial to later creativity. Here’s a quote from him:

Lego, loosely translated, means “to put together” in Latin. But “to put together” doesn’t fully encompass the value – and purpose – of those buckets of colorful bricks. Legos are about putting together, then taking apart, then reassembling in new ways. That’s why I got so upset recently when a friend told me that she and her daughter had built a pirate ship out of Legos, arranged the pieces until they were just right, and then glued the whole thing together. That, I exclaimed, is not the point.

Legos unleashed my creativity when I was growing up. They drew out the part of me that had to know what things looked like from the inside out, how they worked, how they might work better. The hours I spent with them — sprawled on the floor, building and rebuilding, puzzling and visualizing — became my first lessons in engineering. There was magic in those little bricks. There still is.

Reading this I wondered how would Savitz be as an accountant. I think he would have a good chance of being creative, but not in a bad way. I think, like the Lego, he might be throwing away the rule book and creating accounting information which might meet the needs of the organisation where he was working. This of course is what good management accountants should do, but do they all? I don’t know, perhaps its partially our fault (i.e. educators) and we need to encourage lateral (but always ethical and proper) thinking about accounting.

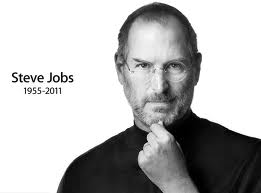

The second article I read was in this week’s Time, “What would Steve do?”. Steve Jobs was an obviously brilliant innovator – and eventually made Apple one of the richest firms in the world. In the article the author (Rana Foroohar) makes a strong claim, but she is probably fairly correct. She states ” Jobs stands out as an exceptional leader not so much because of his in-your-face style, but because American business has become dominated by bean-counters focusing on hyper-efficiency rather than by innovators focused on real growth”. I suppose this is a classic case of too much focus on short-term financial goals over longer-term business development and growth. I don’t have a quick-fix solution for such a problem, but certainly an open mind by accountants towards innovators would help.

What is a “business model”?

Often, when I teach about types and classifications of cost in my management accounting classes, I use the term business model. For example, I might say “whether a cost is fixed or variable, can depend on the particular business model”. But, I am assuming the term business model is well understood. Perhaps it is not, and even when I asked myself what the term means, I had to do a bit of thinking. So here’s a simplified explanation.

Often, when I teach about types and classifications of cost in my management accounting classes, I use the term business model. For example, I might say “whether a cost is fixed or variable, can depend on the particular business model”. But, I am assuming the term business model is well understood. Perhaps it is not, and even when I asked myself what the term means, I had to do a bit of thinking. So here’s a simplified explanation.

An article in the Harvard Business Review from 2002 describes a business model as “the story which explains how an enterprise works”. This is a deceptively simple definition, but it does capture exactly what a business model is. If I were to ask you what are the essential elements of a story such a Cinderella or The Frog Prince, you would probably says things like characters, what the characters do, when the characters do things, and of course the (moss likely) happy outcome. Using the story analogy, a business needs to ask itself, what is that we do, who are our customers, how much does what we do cost, and will we make money (the happy outcome!). In other words, “what’s our story” in an economic sense (Read the full HBR article for more detail and examples).

Nowadays, business models have become a bit blurred though. For example, there are so many web-based “businesses” out there who, to be honest, do not immediately show a story which makes economic sense. For example, we now know how Google and Facebook can make money on a business model which changed the advertising world. But, what about for example Twitter or off-shoots like paper.li. I love the latter, as I can bundle all the twitter users I follow into a daily newspaper, but how can this make money. I am guessing they will introduce advertising, but has this business model already been over-cooked?

I hope this helps you understand what a business model is. To conclude, I suppose the story of what it is a business does has to be infused with accounting concepts. For example, there is not point being the world’s best at something, but costing a fortune to do it.

Using rail freight to reduce CO2 emissions

A year or two ago I set a hypothetical assignment for some of my students on a comparison of CO2 emissions on road freight versus rail freight. I based on the assumption that a CO2 charge would have to be paid by firms, and they could in fact save money by using rail freight. Of course the problem with rail freight is that is does not go door-to-door, but it might still be an option for transporting between cities or depots – depending on volume. At the time when I set the assignment, I did not find many examples (at least in the UK/Ireland), but I came across a Tesco press release in November last. According to the release, Tesco are expanding their use of rail services, which will mean 24,000 tons less CO2 and 72,000 less road journeys. Yes, this is a great thing for the environment, but the management accountant in me really wants to know the cost savings generated by this.

A year or two ago I set a hypothetical assignment for some of my students on a comparison of CO2 emissions on road freight versus rail freight. I based on the assumption that a CO2 charge would have to be paid by firms, and they could in fact save money by using rail freight. Of course the problem with rail freight is that is does not go door-to-door, but it might still be an option for transporting between cities or depots – depending on volume. At the time when I set the assignment, I did not find many examples (at least in the UK/Ireland), but I came across a Tesco press release in November last. According to the release, Tesco are expanding their use of rail services, which will mean 24,000 tons less CO2 and 72,000 less road journeys. Yes, this is a great thing for the environment, but the management accountant in me really wants to know the cost savings generated by this.

The balanced scorecard – making it public??

If you have studied management accounting, you’ll have heard the term balanced scorecard. A scorecard is a report of key performance indicators – both financial and non-financial – of an organisation. Many organisations not only use some form of scorecard, but also publish it on their websites or display it in a public place within the organisation.

If you have studied management accounting, you’ll have heard the term balanced scorecard. A scorecard is a report of key performance indicators – both financial and non-financial – of an organisation. Many organisations not only use some form of scorecard, but also publish it on their websites or display it in a public place within the organisation.

Take for example London’s Heathrow airport. As you can see on the graphic here, they produce a monthly report (see here) which looks at many areas of performance for each terminal. Like many firms, they use a colour-coded system, where red usually means a target has not been achieved – for example, seat availability seems to be an issue in Terminal 3 on the example here.

This scorecard is a great example – if you click the link above you’ll see it has much more than I show here. I have only one negative thing to say about it – and this falls from a recent trip through Terminal 1. I discovered this wonderful colourful (and positive) scorecard on my way to the gents – on the corridor into the toilets to be specific. Surely there’s a better place to display results? Or maybe it does not matter as only us management accountants take any notice of such things.

What is a manufacturing execution system (MES)?

In my former life as a management accountant in industry, I worked in a number of projects which automated either production itself, production planning, or both. A term I was use to at that time was Manufacturing Execution System or MES. So what is an MES and why should management accountants know about them? Well, an advertisement in the November 2011 edition of Financial Management (CIMA’s monthly magazine) prompted me to write about it. AN MES is a system which basically communicates from sales through to the actual making of a product or a the start of a process. An MES may include a sales order module, which would gather customer orders and pass these on to planning modules or directly to process equipment. Typically, an MES will improve a production process as production is scheduled more efficiently and can be monitored for back-logs and jams. Also, an MES will also typically integrate with an ERP system, which means that a businesses systems are fully integrated. According to the advert in the CIMA magazine, Carlsberg (yes the brewer) improved performance in several areas once it used an MES; sales increased bu 1.5%, gross margins up 1.2%, downtime decreased from 28% to 13%, material loss decreased by 1%. All of these translate into increased profitability, which of course is of interest to managers and management accountants. I would argue that understanding how an MES works in a business is a vital piece of kit for any management accountant, particularly if such performance improvements can be made. If you are interested in reading some more, here are two websites I am familiar with which offer MES systems; Kiwiplan and ATS.

In my former life as a management accountant in industry, I worked in a number of projects which automated either production itself, production planning, or both. A term I was use to at that time was Manufacturing Execution System or MES. So what is an MES and why should management accountants know about them? Well, an advertisement in the November 2011 edition of Financial Management (CIMA’s monthly magazine) prompted me to write about it. AN MES is a system which basically communicates from sales through to the actual making of a product or a the start of a process. An MES may include a sales order module, which would gather customer orders and pass these on to planning modules or directly to process equipment. Typically, an MES will improve a production process as production is scheduled more efficiently and can be monitored for back-logs and jams. Also, an MES will also typically integrate with an ERP system, which means that a businesses systems are fully integrated. According to the advert in the CIMA magazine, Carlsberg (yes the brewer) improved performance in several areas once it used an MES; sales increased bu 1.5%, gross margins up 1.2%, downtime decreased from 28% to 13%, material loss decreased by 1%. All of these translate into increased profitability, which of course is of interest to managers and management accountants. I would argue that understanding how an MES works in a business is a vital piece of kit for any management accountant, particularly if such performance improvements can be made. If you are interested in reading some more, here are two websites I am familiar with which offer MES systems; Kiwiplan and ATS.

Know your costs = know your business operations

When I teach management accounting to students, I am always looking for examples to relate what I say to a real life example. So, a while back I was trying to think of an example which might convey the fact that management accountants are not (or should not be) just bean-counters. The role of a management accountant/business analyst/business partner is much more than just accounting. My experience tells me that a good management accountant (and manager too) get’s their hand dirty i.e. knows a good deal about the business in terms of how things are made/delivered. If you don’t know the business, then how for example can you actually undertake a cost-saving exercise. So now for the example. I read a blog post on The Economist website a while back. The title caught my eye actually “Reducing the barnacle bill”. The article post mentions how barnacles attached to a ships hull below the waterline can increase drag so much that fuel costs increase 40%. The post then mentions several chemical solutions currently available and some being worked on. The point from this example is that should a management accountant at a shipping company know such detail of operations. I’d like to suggest, yes they should. Only such detailed knowledge of the operations would highlight the need to control the “barnacle cost”. I’m sure there are many more similar examples out there.

When I teach management accounting to students, I am always looking for examples to relate what I say to a real life example. So, a while back I was trying to think of an example which might convey the fact that management accountants are not (or should not be) just bean-counters. The role of a management accountant/business analyst/business partner is much more than just accounting. My experience tells me that a good management accountant (and manager too) get’s their hand dirty i.e. knows a good deal about the business in terms of how things are made/delivered. If you don’t know the business, then how for example can you actually undertake a cost-saving exercise. So now for the example. I read a blog post on The Economist website a while back. The title caught my eye actually “Reducing the barnacle bill”. The article post mentions how barnacles attached to a ships hull below the waterline can increase drag so much that fuel costs increase 40%. The post then mentions several chemical solutions currently available and some being worked on. The point from this example is that should a management accountant at a shipping company know such detail of operations. I’d like to suggest, yes they should. Only such detailed knowledge of the operations would highlight the need to control the “barnacle cost”. I’m sure there are many more similar examples out there.

Happy Christmas

Just a short post to say I wish you all a very happy and peaceful Christmas and let’s hope 2012 brings joy and happiness too.

Just a short post to say I wish you all a very happy and peaceful Christmas and let’s hope 2012 brings joy and happiness too.

To keep it festive and light-hearted, here’s a line to end the year on (which I found here) – “year-end is approaching – keep calm and carry on reconciling”.

(Picture is the Leipziger Weihnachtsmarkt)

Investment ratios – 5 of 6 in series on financial ratios

As we have seen in an earlier post the ROCE may be useful to shareholders, but there are a number of other ratios which they may find particularly useful as investors. These are Earnings per Share (EPS) and Price Earnings (PE).

As we have seen in an earlier post the ROCE may be useful to shareholders, but there are a number of other ratios which they may find particularly useful as investors. These are Earnings per Share (EPS) and Price Earnings (PE).

EPS represents the profit per individual share. It as calculated as follows:

EPS: Profit after tax, interest and preference dividends

Number of ordinary shares in issue

The top portion of the EPS ratio represents the profit that is available for payout as a dividend. This does not at all mean it will be paid out, but it is the profit available to ordinary shareholders. Given that the bottom portion of the EPS is the number of ordinary shares issued, the EPS is not very comparable between two companies. However, the trend of the EPS of a particular company is an important indicator of how well the company is performing and it is also an important variable in determining a shares price

The PE ratio shows a company’s current share price relative to its current earnings – which assumes the company is a public company and its shares are available for purchases through a stock market. It is calculated as follows:

P/E ratio: Market price per share

Earning per share

It’s usually useful to compare the P/E ratios of one company to other companies in the same industry, to the market in general, or against the company’s own P/E trend. It would not be useful for investors to compare the P/E of a technology company (typically high P/E) to a utility company (typically low P/E) since each industry has very different growth prospects. Care should be taken with the P/E ratio because the bottom part of the ratio is the EPS, which as stated above may not be that comparable between companies. There are some crude yardsticks for the P/E ratio as follows:

- A P/E of less than 5-10 means that company is viewed as not performing so well;

- A ratio of 10-15 means a company is performing satisfactorily;

- A ratio above 15 means that future prospects for a company are extremely good.

Again, as with all such yardsticks, these will vary by industry and depend on other factors which drive share price e.g. bad publicity, the general economic outlook.

As in previous posts, let’s use the accounts of Diageo plc from 2010 to calculate these ratios.

EPS = 1,762,ooo/2,754,000 = £0.64 per share (data from p. 107/150)

PE = 1060/64 = 16.6 times (share price from http://www.diageo.com/en-row/investor/shareprice/Pages/Shareprice-History.aspx. Based on the yardstick mentioned above, the PE for Diageo reflects sound future prospects.

Working capital management ratios – 4 in series of 6 on financial ratios

In this post, I’ll detail some ratios which can helps a business manage its working capital (working capital is current assets less current liabilities). A business can calculate a ratio for each of inventory, trade receivables, and trade payables which help interpret how well working capital is managed. In my previous post, I showed some ratios which help determine liquidity and solvency; with the ratios below, we have all elements of working capital covered (including cash) .

In this post, I’ll detail some ratios which can helps a business manage its working capital (working capital is current assets less current liabilities). A business can calculate a ratio for each of inventory, trade receivables, and trade payables which help interpret how well working capital is managed. In my previous post, I showed some ratios which help determine liquidity and solvency; with the ratios below, we have all elements of working capital covered (including cash) .

The first ratio is inventory turnover, which is calculated as follows:

Inventory turnover: Cost of sales

Average inventory

This ratio tells us how many times a year inventory is sold. You’ll notice the bottom line says “average inventory”, which might be a simple average of the inventory at the start of the year and the end of the year, or a rolling average. The reason for using an average is to try to remove seasonal variations.

The next ratio reflects how well trade receivables are managed:

Average period of credit given: Trade receivables x 365

Credit sales

This ratio tells how many days credit, on average, is given to customers. The top line is multiplied by 365 to give the answer in days. If you want it in months, multiply by 12 instead. If the period of credit given is getting longer, this could be problematic, as cash is not collected as fast by the business.

Now let’s see the average period of credit taken. This is very like the previous one, except it relates to suppliers. It is calculated as follows:

Average period of credit taken: Trade payables x 365

Credit purchases

One thing to note about this ratio is that it may not always be possible to obtain the credit purchases figure from published financial statements. The period of credit taken should not be too long either. If it is getting longer, it may be a sign of cash flow problems.

As in my previous posts, I’ll now calculate the above ratios using the figures from the 2010 annual report of Diageo plc.

The inventory turnover is: 4099 (3281+3078)/2 = (data from p.106/108) =1.2 times per annum. This means the company sells its inventory just over once per year. This probably seem really low if you think about how quickly beer and other alcohol sells in a retail sense. However, if we look at the detailed notes on inventory in the annual report, we can see that about 2/3 of the inventory is deemed “maturing” inventory.

The average period of credit given is: 1495 x365/9780 = 56 days (data from p.106/140). This seems a reasonable period of credit.

The average period of credit taken is: 843 X 365/4099 ) =75 days (data from p.106/148). Note that I am using the cost of sales figure as a substitute for the credit purchases figure – which is typically not available in published accounts. Again this figure seems reasonable and is longer than the period of credit given, which makes logical sense.

In summary from the figures above, the working capital of Diageo plc seems well managed.

Liquidity ratios – 3 in series of 6 on financial ratios

Your have probably heard the terms liquidity and solvency. Liquidity refers to the ability to convert assets to cash. For example, inventories may be more liquid (i.e. can be sold for cash quicker) than a non-current asset like a building. Solvency refers to the ability of a business to pay debts as they fall due. Liquidity and solvency are closely related concepts. If assets cannot be converted to cash, debts like loan repayments or payments to suppliers may not be met. To be unable to pay debts as they fall due means a business is insolvent, which can mean business failure. There are two useful ratios to help us assess the state of a businesses’ liquidity – the current ratio and the quick (or acid-test) ratio. The current ratio is:

Your have probably heard the terms liquidity and solvency. Liquidity refers to the ability to convert assets to cash. For example, inventories may be more liquid (i.e. can be sold for cash quicker) than a non-current asset like a building. Solvency refers to the ability of a business to pay debts as they fall due. Liquidity and solvency are closely related concepts. If assets cannot be converted to cash, debts like loan repayments or payments to suppliers may not be met. To be unable to pay debts as they fall due means a business is insolvent, which can mean business failure. There are two useful ratios to help us assess the state of a businesses’ liquidity – the current ratio and the quick (or acid-test) ratio. The current ratio is:

Current ratio: Current assets

Current liabilities

The basic idea the current ratio is that for a company to be able to pay its debts as they fall due, current assets should cover current liabilities by a multiple. Generally a current ratio of at least 2:1 is good. This means that current assets are twice current liabilities. So, even if some stock could not be sold or some trade receivables not paid, current liabilities would still be covered for payment. However, the 2:1 figure is only a guideline. If we calculate the current ratio for Diageo plc for 2010 (from the statement of financial position on p. 108), we get:

6,952/3,944 = 1.76 : 1.

Although not 2:1, it should not be a major problem. Think about the type of business and the inventory it has – can you imagine Diageo having difficulty selling it’s stock of Guinness for example.

The Liquid ratio, and it is calculated as follows:

Liquid ratio: Current assets – inventory

Current liabilities

This ratio is also called the Quick ratio or the Acid Test ratio. It is very similar to the Current ratio, except that inventory is deducted from current assets. This is because inventory is typically regarded as being the least liquid current asset. Often the yardstick for the Liquidity ratio is 1:1, but this depends on the type of business. For example, large retailers may have relatively low stock and almost no receivables, which will skew the figure well below zero if we assume suppliers give credit.

If we calculate the current ratio for Diageo plc for 2010 (from the statement of financial position on p. 108), we get:

6,952-3,281/3,944 = 1.12 : 1

The Current and Liquid ratios serve as useful indicators of the liquidity/solvency or a business. However, as with other ratios, the trend over time is important. Any business may face short-term liquidity problems which could skew either of the above ratios. Short-term liquidity problems may arise if, for example, customers are slow to pay or inventories can’t be sold. Such problems are normally overcome through the management of inventory and receivables, which I’ll deal with in the next post.

(Image above from withfriendship.com)

Single entry accounting

Elsewhere on my blog, I have written a post of the basics of the double entry accounting system. I had a comment on this post asking for some more information on single entry accounting – so here it is.

Elsewhere on my blog, I have written a post of the basics of the double entry accounting system. I had a comment on this post asking for some more information on single entry accounting – so here it is.

The basic idea of the double entry accounting system is that information is recorded twice. The system allows any business or organisation to get a picture of its incomes, expenditures, assets, liabilities and capital at any point in time. The double entry system is encoded into all accounting software and is the basis of all financial reports of businesses.

In the double entry system, any transaction is recorded from its source all the way through to the financial statements. For example, if a supplier is paid the following happens:

- the cheque is recorded in a “day book” – normally a cash/cheque payments book

- the suppliers balance is updated – in a personal ledger account

- the bank balance is updated

- by virtue of the previous two items, the assets (bank) and liabilities (trade payables) are updated

- the financial statements (income statement and balance sheet) are updated.

In a single entry system, some of the above is not done. The best way to explain this is by an example. When I worked in small accounting firm some years ago, most sole traders kept what were single entry records. At that time (the early 1990’s) most small sole traders kept records in a manual form – most had no computer anyway. The records would typically comprise a book where all purchases/expenses were recorded, a book where all payment in and out of the bank were recorded and a book where all sales were recorded. Records of things like assets – how much was owed by customers or records of vehicles for example – and liabilities – how much was owed to suppliers for example – were not kept. Using these books, it is only possible to prepare an income statement. Thus, as the double entry system is not applied in full, i.e. transactions are not recorded through ledgers in this example, then the single entry system applies.

It is not possible to say that the single entry system means that only certain specific records are kept. It’s probably better to think of the single entry system of accounting as one which does not fully use the principles of double entry, but does allow profit to be calculated. In the example above, what we did was to build up a list of the assets and liabilities, as well as the capital of the business, to allow us to prepare an income statement (profit and loss account) and statement of financial position (balance sheet).

Knowing the cost structure of your business

When a business or manager refers to their cost structure, they are talking about the composition of the costs of the business. Typically, costs are either fixed or variable. Fixed costs stay the same regardless of what happens e.g. how much is sold. Variable costs increase or decrease in line with business activity e.g. the more product sold, the higher the purchase or manufacturing costs. It goes without say that a business manager needs to have a full knowledge of how their business responds to changes in output and how the business itself actually operates. I read a great example of this back in June this year in the Guardian. The article mentioned how Ryanair had started talks with a Chinese aircraft manufacturer (Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China) in an effort to build a cheaper alternative to its current aircraft, the Boeing 737. What struck me was not the cheaper cost of the aircraft, but attempts by Ryanair to design the aircraft with exactly 200 seats – about 15 more than the Boeing. Why 200 seats? Simple answer actually, anything above 200 seats and one additional crew member is needed. Keeping the seats at 200 means that each extra seat could yield anaverage profit of about €40 per seat. Now that’s knowing your cost structure and operations in detail

When a business or manager refers to their cost structure, they are talking about the composition of the costs of the business. Typically, costs are either fixed or variable. Fixed costs stay the same regardless of what happens e.g. how much is sold. Variable costs increase or decrease in line with business activity e.g. the more product sold, the higher the purchase or manufacturing costs. It goes without say that a business manager needs to have a full knowledge of how their business responds to changes in output and how the business itself actually operates. I read a great example of this back in June this year in the Guardian. The article mentioned how Ryanair had started talks with a Chinese aircraft manufacturer (Commercial Aircraft Corporation of China) in an effort to build a cheaper alternative to its current aircraft, the Boeing 737. What struck me was not the cheaper cost of the aircraft, but attempts by Ryanair to design the aircraft with exactly 200 seats – about 15 more than the Boeing. Why 200 seats? Simple answer actually, anything above 200 seats and one additional crew member is needed. Keeping the seats at 200 means that each extra seat could yield anaverage profit of about €40 per seat. Now that’s knowing your cost structure and operations in detail

Business lessons from Apple

Here is a really good article from Forbes on what other businesses could learn from the legacy of Steve Jobs – and to the man’s testament this is posted from an iPhone at my kitchen table. Read the piece here

Data theft cost Sony as much as earthquake

I remember some meetings in my past life, when I had to justify expenditure on information to my boss – a chartered accountant with not too much in-depth knowledge of IT. This was in the late 1990’s. Of course, technology has moved on dramatically since then, but I’d be fairly sure that any accountants today would still be questioning the costs if IT/IS infrastructure and software. And today, it is not only the cost of the equipment that needs to be considered, it is the cost of the information held by companies. This is a very difficult thing to cost, but the problems at Sony in recent months gives some idea. In May 2011, the Los Angeles Times wrote about the cost of the first hacker attack on Sony (there was another one in June 2011). The article reports a cost of $171 million, which is believe it or not is nearly as much as the impact of the Japanese earthquake/tsunami earlier that year on the companies profit ($208m). I’m not sure what the hackers did to break in to Sony’s systems, but I bet it would have cost a lot less than $171 million to make their systems hacker-proof. And I’d also bet the hacker’s would be happy to repair the damage for a lot less than $171 million too!

I remember some meetings in my past life, when I had to justify expenditure on information to my boss – a chartered accountant with not too much in-depth knowledge of IT. This was in the late 1990’s. Of course, technology has moved on dramatically since then, but I’d be fairly sure that any accountants today would still be questioning the costs if IT/IS infrastructure and software. And today, it is not only the cost of the equipment that needs to be considered, it is the cost of the information held by companies. This is a very difficult thing to cost, but the problems at Sony in recent months gives some idea. In May 2011, the Los Angeles Times wrote about the cost of the first hacker attack on Sony (there was another one in June 2011). The article reports a cost of $171 million, which is believe it or not is nearly as much as the impact of the Japanese earthquake/tsunami earlier that year on the companies profit ($208m). I’m not sure what the hackers did to break in to Sony’s systems, but I bet it would have cost a lot less than $171 million to make their systems hacker-proof. And I’d also bet the hacker’s would be happy to repair the damage for a lot less than $171 million too!